2022 marked the 100th anniversary of the Association's advocacy in Native Country!

|

Over 100 years ago, the United States asserted policies of violence, genocide and assimilation to end the “Indian problem.” The problem, truly, was that Natives continued to possess their sovereignty, lands and resources reserved and protected by treaties and other federal laws. Secondarily, their diverse cultural and religious practices were “contrary” to Christianity. The movement to “kill the Indian and save the man” sought to rid Native Peoples of their identity, imposed boarding schools and adoption of Native children into white homes, outlawed cultural practices, religions and languages and eradicated traditional foods and medicine sources.

Many Native leaders say that without the efforts of the Association, Native Nations would not possess the self-determination, sovereignty and strength they do today. But there is still more work that needs to be done. To honor a century of protecting Native Cultural Sovereignty, learn more about the Association’s work over the last more than 100 years and join with us as we create a world where diverse Native cultures and values are lived, protected and respected. |

The Association’s efforts over the last over 100 years have always begun on the ground, hand-in-hand with Native Nations. Stories of the Association’s advocacy and Native Country victories – as well as stories of loss – provide education and hope for our next 100 years of continued grassroots campaigns.

|

Story of the Association

1920's: Stopping Assimilation

At a time when federal Indian policy was genocide through the theft of Tribal lands, the outlaw of Native religious and cultural practices, boarding schools and other assimilation policies, the founders of the Association stood up to protect sovereignty, preserve culture, educate youth and build capacity.

|

1923: The Association fought against the passage of the Leavitt Bill, aka the Dance Order, that outlawed the Pueblo Nations’ from practicing their traditional dances, which are part of their cultural and religious practices. The bill did not pass thanks to the important advocacy of the Association hand-in-hand with the Pueblo Nations. Learn more about the Leavitt Bill. |

1922: The Association advocated nationally before Congress, Native Nations, and the general public to fight against the passage of the Bursum Bill. The bill threatened an estimated 60,000 acres of Pueblo Homelands and jurisdiction of Pueblo water rights. After successful defeat of the Bursum Bill the Association supported the development of legislation that protected Pueblo Lands with the Pueblo Lands Act of 1924.

Learn more about the Bursum Bill. |

|

1928: The Association gathered facts and data to show Bureau of Indian Affairs abuses in the Meriam Report. Native Nations were reluctant to work with federal agents but willingly partnered with the Association to give accurate insight into the human rights struggles they were enduring at the hands of the federal government. Learn more about the Meriam Report. |

1930's: The Beginnings of Rectification

After the Merriam Report in 1928, the egregious failures of assimilation policies were finally on paper and it was time for the federal government to take corrective action. That corrective action included ending allotment and restructuring Tribal governance and education. The founders of the Association worked to improve government facilities, educational opportunities and worked with Native Nations to develop written constitutions to form westernized governance systems. Though these governance systems have been problematic, the work gave Native Nations tools to protect their sovereignty and land base.

|

1934-1936: The Association was working to end boarding schools in the 1930s! With John Collier in the Office of Indian Affairs, the Association developed a memorandum to advance Tribal education promoting bilingualism, crafts, art, literature, music, Tribal governance, tradition, agriculture, sheep husbandry, resource development and subsistence. The memo discussed initiatory procedures to abolish boarding school facilities and the development of day schools.

Learn more about the damage of boarding schools on Native children. |

|

1935: The Association was instrumental in the passage of the original Indian Arts & Crafts Act of 1935. The Association worked with Tribes to understand the issues and to make sure the act's language favorably benefitted Tribal Nations and Native Peoples. With the passing of this bill and the establishment of the Arts and Crafts Board, Tribes have, ever since, been better able to preserve the integrity of their creations for the public. Learn more about the importance of the Indian Arts & Crafts Act. |

|

1938: The Association worked hand-in-hand with the Pyramid Lake Paiute Tribe to stop a bill that would give non-Indian squatters rights to 2,000 acres of protected lands and water. A bill was introduced to legitimize these squatters' claims. The Association kept pressure on to stop the bill, though in the next decade, the same political leaders in Congress kept trying to stead Pyramid Lake Paiute lands and water.

Learn more about how the Association helped preserve this Sacred Lake. |

1940's: World War II, Discrimination and Suffrage

|

Learn more about Native American contributions in the U.S. military here:

|

1941-1945: At the outbreak of World War II, propaganda from Germany reached American shores, promising Native Americans the return of their lands should they revolt against the United States. Nonetheless, Tribes across the country overlooked the disappointing relationship with the United States government and considered the defense of their homelands a greater importance.

In numbers larger than any other group, Native Americans rallied to the war effort, contributing land and resources, buying war bonds, planting Victory Gardens and enlisting and volunteering for a variety of positions in the military. Local draft boards took into consideration language barriers and cultural confusion when communicating with Tribes. The Association worked with the Hopi Nation and other Tribes about what the draft required of them. To this day, Native Americans enlist in the military at higher rates than any other ethnic group, enlisting at a rate 5 times the national average. |

|

1948: Through the Indian Citizenship Act of 1924, all Native Americans were unilaterally given the right to vote. However, the Act did not guarantee the right to vote in state elections.

In New Mexico and Arizona, Native Americans were denied the right to vote on the basis of the state constitution that ‘Indians not taxed may not vote.’ In 1948, the Association’s general counsel, Felix Cohen filed an Amicus brief to defend their Native voting rights. He successfully argued the landmark case in New Mexico, Trujillo v Garley, securing the Native American right to vote in those states. Learn more about Native American voting rights here: |

|

1948: New Mexico and Arizona had denied Tribes within their boundaries social security, defying the Federal Social Security Act. The states justified the denial of benefits on the argument that if benefits were extended to Native Americans, the payments to all beneficiaries would be reduced. This was clear discrimination.

The Association filed suit in the case of Mapatis et al v Krug, Ewing, et al. on September 21, 1948. The Association also created petitions that were addressed to President Truman, the Secretary of the Interior and the Federal Security Administrator, specifically requesting the termination of these racially discriminatory policies conducted by state governments. The litigation was decided in favor of Tribes and social security benefits were paid. Learn more about taxation of Native Nations. |

1950's: Termination, Death Penalty and Land-Leases

The 1950’s were largely defined by Congressional pursuit to end all federal obligations to Native Nations. Greater anti-socialist and anti-communist sentiments across the country impacted the policy changes. The federal relationship to Native Nations became an illustration of the collectivist threat to American ideals.

The betrayal felt amongst Native Nations was profound as their land and resources were once more vulnerable for the taking. Though no one was successful to block the progression of termination policies, the Association was able to delay termination dates and amend terms for several Tribes. The Association continued to work to end termination and return those Nations terminated back to their original government-to-government relationship with the United States.

The betrayal felt amongst Native Nations was profound as their land and resources were once more vulnerable for the taking. Though no one was successful to block the progression of termination policies, the Association was able to delay termination dates and amend terms for several Tribes. The Association continued to work to end termination and return those Nations terminated back to their original government-to-government relationship with the United States.

|

1954: Loyd Grandsinger, a Native man from the Ogalala Sioux, was convicted of first-degree murder in Nebraska.

It was believed that his constitutional rights had been violated and the Association filed for a 60-day writ to postpone his death sentence two weeks before his execution. This allowed time for the defense to prepare a petition for writ of certiorari. The Association was successful and the court found that the trial and conviction brought against Loyd was unconstitutional. Learn more about Native American prisoners’ rights and statistics here: |

|

1955: The Association advocated passing the Long-Term Land Leasing Act before Congress to elevate the welfare of Native Americans. The Association learned from its work in Indian Country that economic success was being thwarted for Native Americans and their Nations because the federal government would not allow land leases for more than 5 years. Land leasing allows Native and non-Native businesses to develop economic enterprises within Indian Country, for which there are many benefits for the Tribe and the business.

In 1955, Congress passed the law permitting leasing of up to 25 years with the approval of the Secretary of the Interior. Today, the federal government must still approve land leases in Indian Country. The Helping Expedite and Advance Responsible Tribal Home Ownership Act of 2012 (HEARTH Act) offers a voluntary, more efficient land-leasing process for Tribes by amending the Indian Long-Term Leasing Act of 1955, 25 U.S.C Sec. 415. However, Tribes must still obtain approval from the Secretary of the Interior according to federal standards. Thus, Tribes still do not have control over their land uses. |

|

1957: The “We Shake Hands” program was developed by several Great Plains Tribes to encourage positive relationships with surrounding non-Native communities in the area. As federal policies trended towards termination, the Association supported the program as a strategy to strengthen Native Nations against the taking of more Native lands.

The program provided economic development opportunities for the Northern Cheyenne Tribe that included buying back land, establishing a cattle enterprise, building a small factory and creating a tourist center. The Association guided these efforts by transmitting loan requests and program proposals to the Department of the Interior. Learn more about the We Shake Hands program here.

|

1960's: Alfred Ketzler, Alaska Land Grabs and the Tundra Times

|

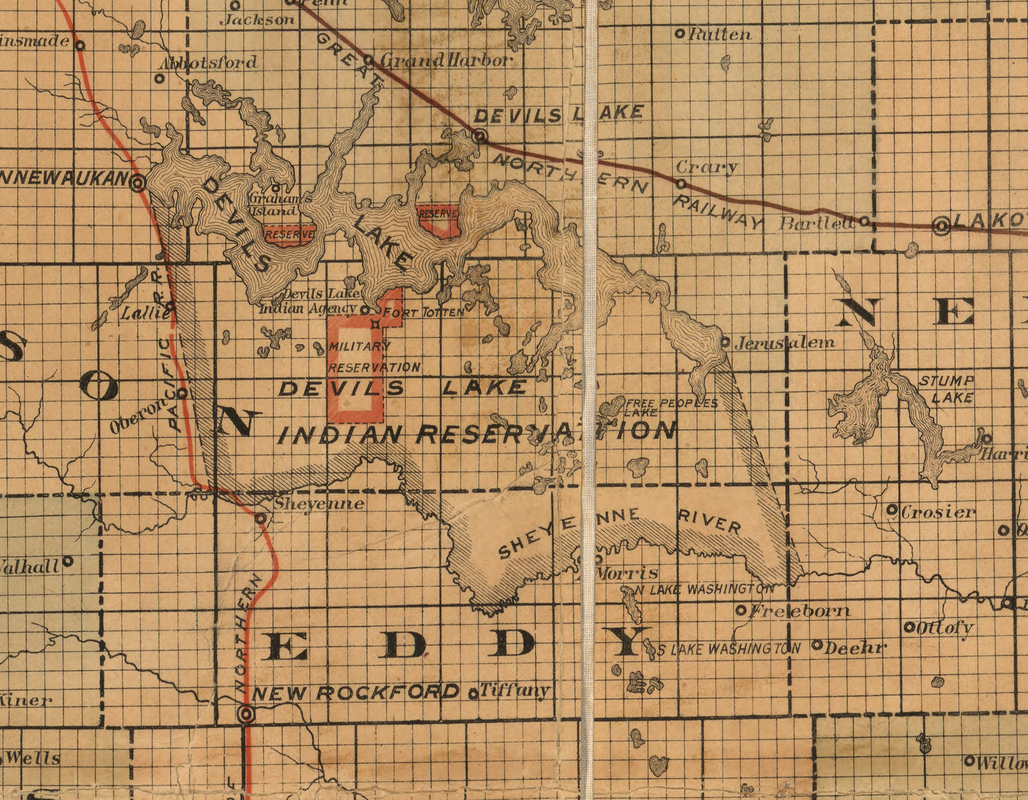

In the early 1960s, Lewis Goodhouse, Tribal Chairman of the Spirit Lake Sioux of North Dakota, reached out to the Association seeking help to improve the living conditions on the reservation.

William Byler, Executive Director of the Association, responded by traveling to North Dakota along with staff attorney Bertram Hirsch to meet with the people of Spirit Lake to find the best ways to serve them. The Association assisted them with projects that improved their water supply and housing conditions. |

|

1961: the Association first came into contact with Alfred Ketzler, who was at the forefront of the Alaska Native land rights movement, spearheading much of the advocacy to protect aboriginal title to the land. In June 1962, Alfred helped organize a meeting of 32 villages at Tanana. The Association contributed to Alfred’s efforts by aiding with the cost of transporting the Chiefs of Tanana, ensuring their attendance. At the meeting, participants formed a regional organization called Dena’ Nena’ Henash, “Our Land Speaks.” This organization later went on to become Tanana Chiefs Conference, although it was not formally incorporated until 1971. The Tanana Chiefs Conference formed as an Alaska non-profit corporation, with the mission of advancing Tribal self-determination and enhancing regional Native unity. Alfred served as Chairman for Dena’ Nena’ Henash, and later became the first President of the Tanana Chiefs Conference.

A suggestion that came from the first Conference in Barrow, was the creation of a newspaper or bulletin to be circulated through Alaskan Villages as a means of disseminating relevant information. By October 1, 1962, the first Tundra Times editorial was released and announced: Natives of Alaska, the Tundra Times is your paper. It is here to express your ideas, your thoughts and opinions on issues that vitally affect you…With this humble beginning we hope, not for any distinction, but to serve with dedication the truthful presentation of Native problems, issues, and interests. The newspaper was created by Alfred along with two other Alaskans, Howard Rock, who became the editor of the newspaper, and his assistant, Tom Snapp. Dr. Henry Forbes from the Association was the sponsor of this newspaper. The Tundra Times was controlled and edited by Alaskan Natives to help strengthen and unify their voices, but also to help keep villages informed. Alfred was quoted in a Washington Post article as saying “Before we started this newspaper, there was little communication among the natives in these widely separated villages, especially the interior… many of them weren’t being informed about the land grab.” Alfred was one of the first people to propose Congressional action to “fight land grabs” rather than going to court. |

1970's

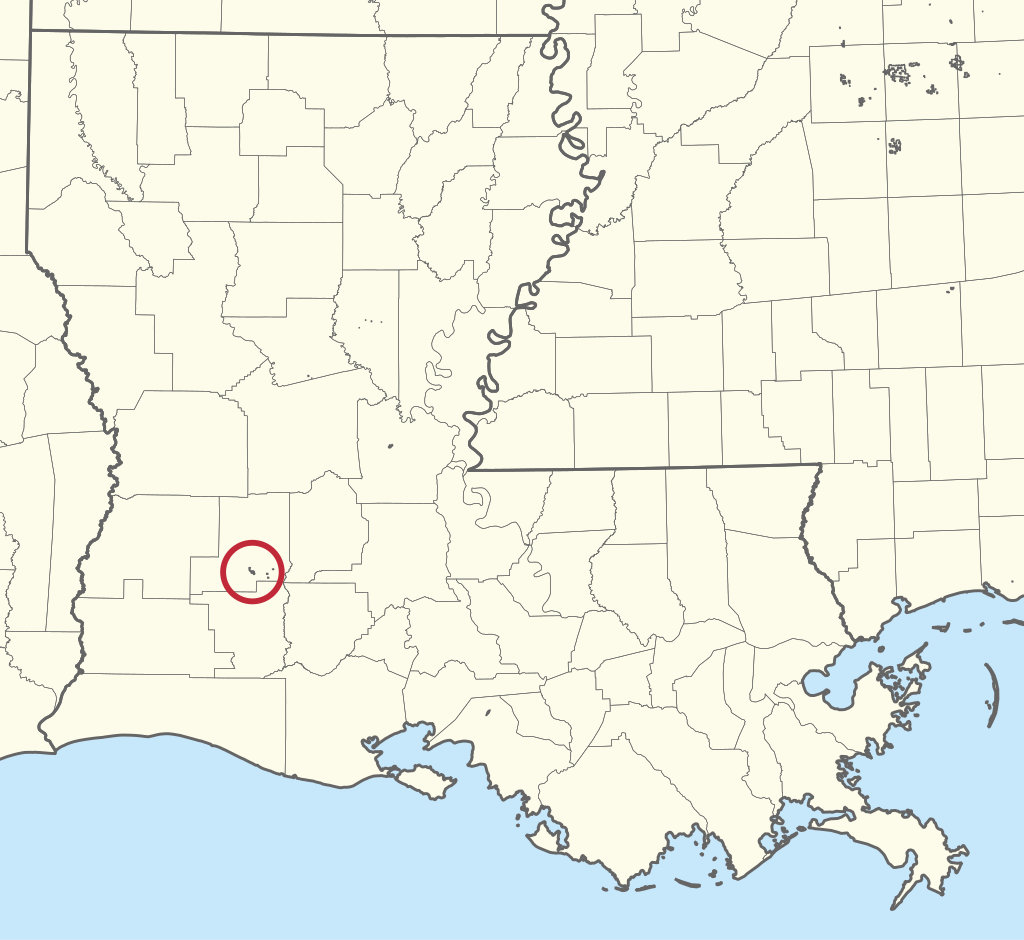

Coushatta Tribe Federal Recognition

|

1973: The Coushatta, who historically had resided in Alabama territory, did not migrate to Louisiana until 1795. Though relations with French and Spanish colonizers in the 18th century had been tense, the Treaty of Paris in 1783 began a period of increased violence, of territorial seizure and invasion. A treaty was created that seized 800 square miles from the Tribe. As increasing plots of land were turned over to the government via treaties, the Coushatta abandoned their land and migrated across states. They joined other Tribes in the Creek War of 1813-14. The war, fought with the Muskogee Family of Tribes, was ultimately lost. They then followed the Coushatta leader, Red Shoes, to Louisiana.

In 1898, the US government placed 160-acres in a trust. In the 1930’s they were briefly recognized by the Bureau of Indian Affairs and awarded educational services. This, however, was short-lived and the Termination policies in the 1950’s ended these programs. In 1972, they won recognition in the Louisiana legislature. Using Bureau of Indian Affairs requirements as a guideline, they formed a corporation, drafted a constitution and bylaws. |

Bobo Dean, an attorney who worked for the Association, guided the President of the Coushatta Alliance through the forms necessary to file with the IRS for recognition as a tax exempt organization. He offered to review the documents prior to submission to ensure efficient processing. The Association assisted with the fee payment required for amending Articles in the Coushatta Constitution. The Association contacted a Louisiana law firm, Cox, Cox and Grand, to request further assistance for establishing the Coushatta Tribe and paid the legal fees incurred. As the title of the Tribe was being finalized by the attorneys of the Secretary of the Interior, Bobo Dean completed the remaining papers necessary to transfer the land to a trust.

However, the Bureau of Indian Affairs countered the Coushatta claim by requiring the Tribe have possession of at least 25-acres to be eligible for federal recognition. Bobo Dean wrote to the Bureau of Indian Affairs, accusing them of ‘flagrant abuse of administrative discretion’, due to the lack of a ‘single explanation of …action which bears the scrutiny of reason’ why they refused to approve the contract. The Bureau argued that there was no ‘land base’ that was required for tribal government development. This argument was in direct conflict with the statement of the Acting Commissioner of Indian Affairs, who in 1973, confirmed that the Coushatta Tribe was eligible for Bureau programs and that land base was not a requirement. Bobo appealed the decision to the Commissioner of Indian Affairs.

While the Association worked to appeal the ruling, they also assisted in obtaining land. With the land requirement met, the Coushattas would then be able to qualify for self-government. The Tribe was able to obtain 10-acres. The Association purchased 25-acres for the Tribe. They petitioned the US government to accept that land in trust. By pressuring the Bureau and purchasing land, the Association was ultimately able to successfully obtain full Tribal status for the Coushatta in 1973. Bobo Dean submitted tax receipts to the Bureau of Indian Affairs to confirm the property taxed had been paid and the establishment of the reservation had been solidified.

However, the Bureau of Indian Affairs countered the Coushatta claim by requiring the Tribe have possession of at least 25-acres to be eligible for federal recognition. Bobo Dean wrote to the Bureau of Indian Affairs, accusing them of ‘flagrant abuse of administrative discretion’, due to the lack of a ‘single explanation of …action which bears the scrutiny of reason’ why they refused to approve the contract. The Bureau argued that there was no ‘land base’ that was required for tribal government development. This argument was in direct conflict with the statement of the Acting Commissioner of Indian Affairs, who in 1973, confirmed that the Coushatta Tribe was eligible for Bureau programs and that land base was not a requirement. Bobo appealed the decision to the Commissioner of Indian Affairs.

While the Association worked to appeal the ruling, they also assisted in obtaining land. With the land requirement met, the Coushattas would then be able to qualify for self-government. The Tribe was able to obtain 10-acres. The Association purchased 25-acres for the Tribe. They petitioned the US government to accept that land in trust. By pressuring the Bureau and purchasing land, the Association was ultimately able to successfully obtain full Tribal status for the Coushatta in 1973. Bobo Dean submitted tax receipts to the Bureau of Indian Affairs to confirm the property taxed had been paid and the establishment of the reservation had been solidified.